ter1413

Stylish Dinosaur

- Joined

- Dec 3, 2009

- Messages

- 22,101

- Reaction score

- 6,033

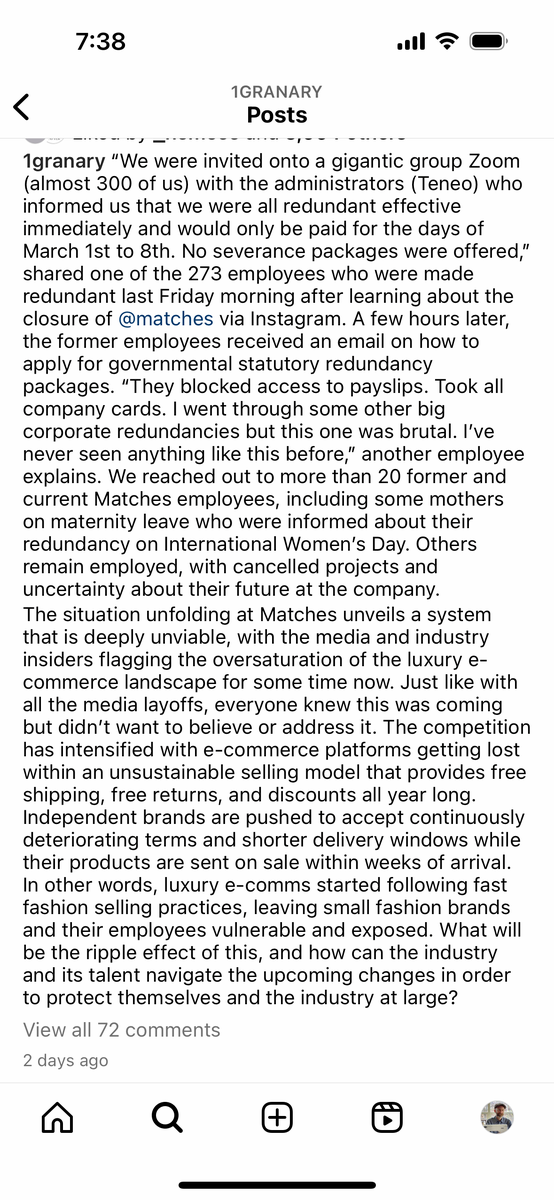

How Menswear Maestro Umit Benan Became One of Milan’s Most Exciting Designers

A tastemaker to tastemakers, the Turkish designer seems increasingly disinterested in the notion of “fashion.”