VRaivio

Distinguished Member

- Joined

- Jul 8, 2011

- Messages

- 2,459

- Reaction score

- 892

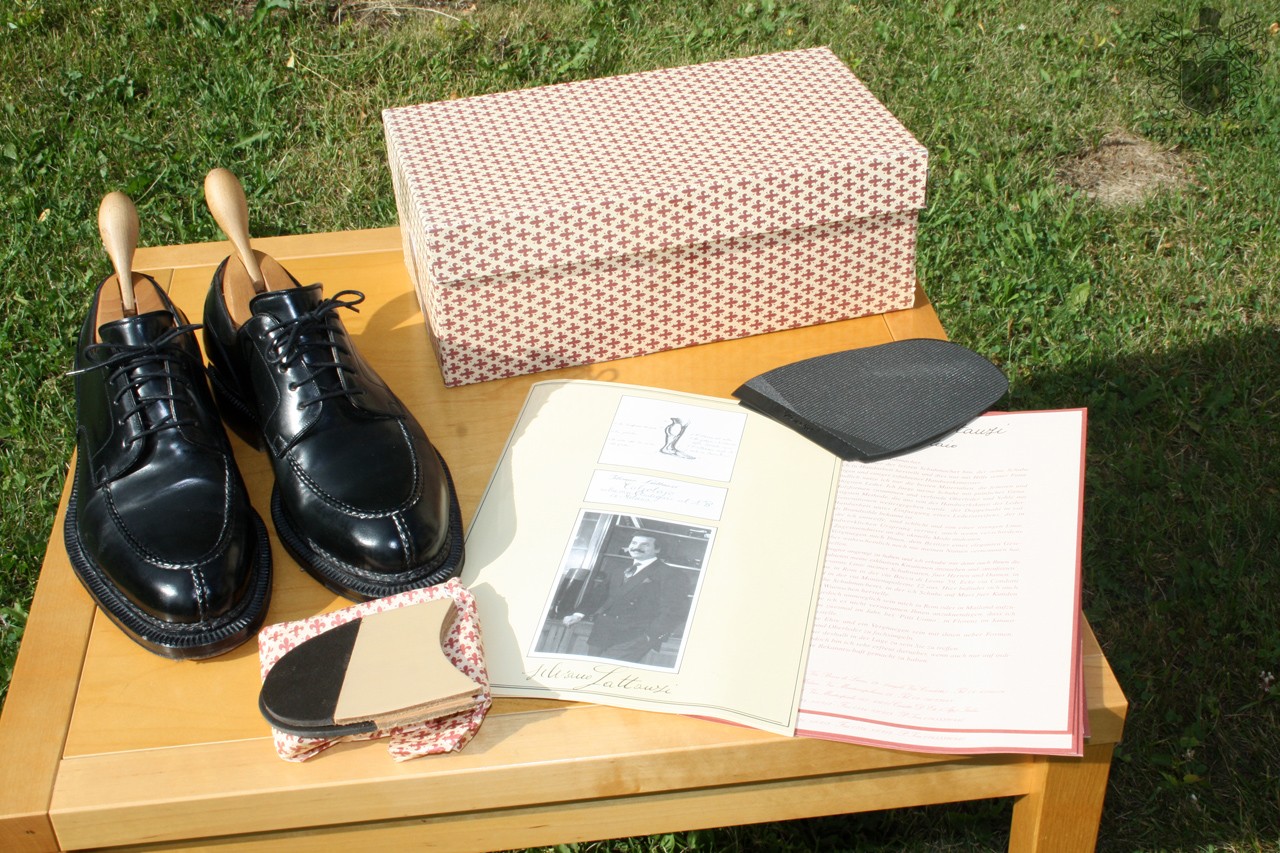

...so I searched and, to my surprise, there isn't a definitive thread for the art of SL. I've seen several pairs from various members so I'm sure there's room for discussion. With the update of their site, there's now dozens of bespoke samples and many RTW pairs for ogling.

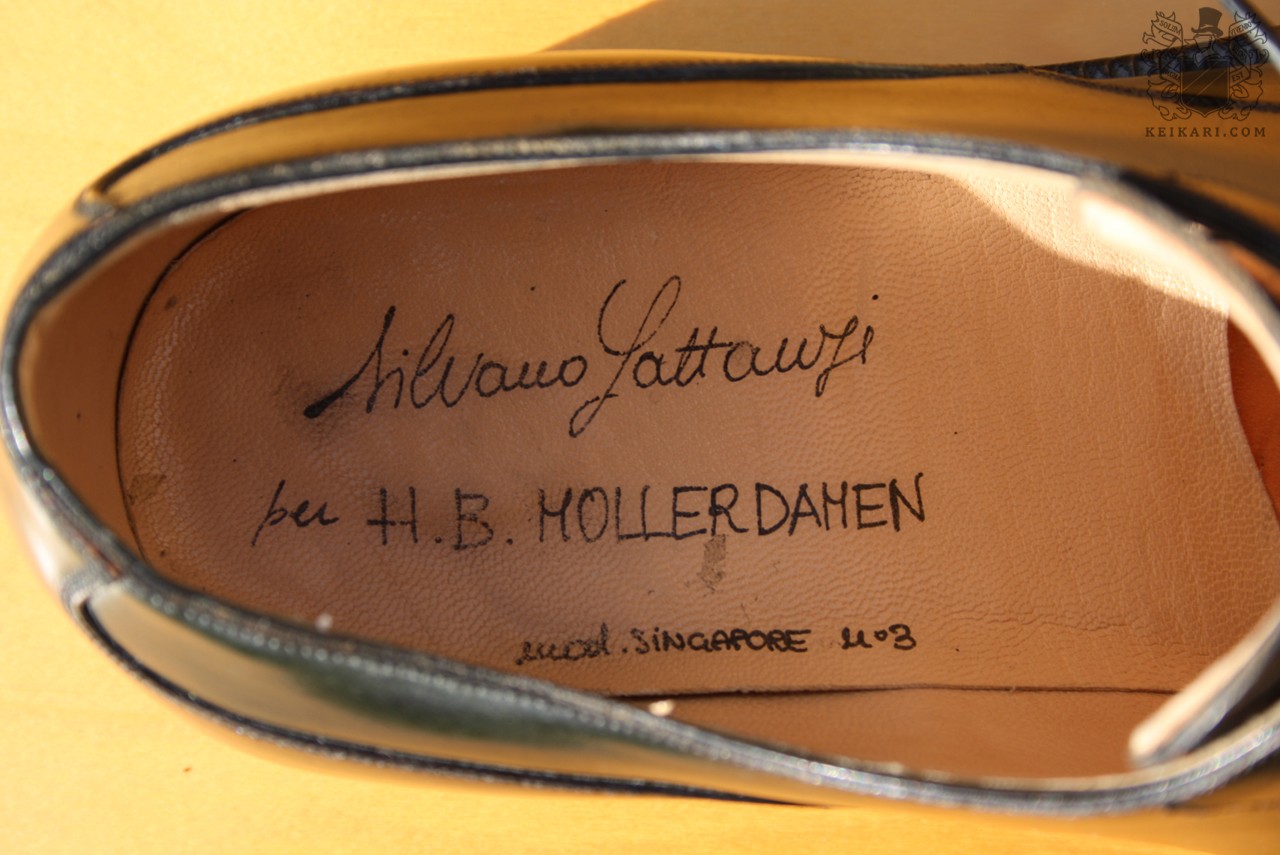

For a jump start, here's one pair from my collection: mid-brown shell cordovan penny loafers with Norvegese stitching, heavy welts, double oak soles, split toe and a suprising hourglass stiching on the penny strap.

For a jump start, here's one pair from my collection: mid-brown shell cordovan penny loafers with Norvegese stitching, heavy welts, double oak soles, split toe and a suprising hourglass stiching on the penny strap.

Last edited: