- Article Format

- Article View

By Andrew Yamato

The first film to win the “Big Five” Oscar awards - Best Picture, Actor, Actress, Director, and Screenplay - It Happened One Night [1934] actually happens over several nights of a bus, automobile, and shoe leather journey from Miami to New York, undertaken by Clark Gable’s hard-boiled newshound Peter Warne and his journalistic quarry Ellie Andrews - a runaway heiress played with iconic pluck by Claudette Colbert. This is the movie everyone knows for having collapsed undershirt futures when Warne undresses to reveal a bare chest, but its real sartorial significance lies not in what Gable doesn’t wear, but in what he does. His attire throughout the film is a case study in the form and function of classic menswear, not least because the film was a commercial blockbuster, doing much to set the style for a decade that’s set the style ever since.

From a wainscoted yacht off Miami, to bustling modern cities of news stands and phone booths, to bucolic idylls of moonlit haystacks and general stores, to a formal garden wedding at a baronial estate, It Happened One Night’s locales make it something of an Apparel Arts travelogue, as atmospherically rendered and elegantly populated as Laurence Fellows’ idealized illustrations. It is perhaps a road movie even before it’s a screwball comedy or even a love story, and the style of its male protagonist is suffused with the giddy romance of a mode of travel only recently made possible by the internal combustion engine. The act of traveling today may conjure little but fast food and flight delays, and the clothes we wear to endure it tend to be chosen largely as comfortable swaddling, but watching Peter Warne make his way up the eastern seaboard and into Ellie Andrews’ heart reminds us that it doesn’t have to be this way.

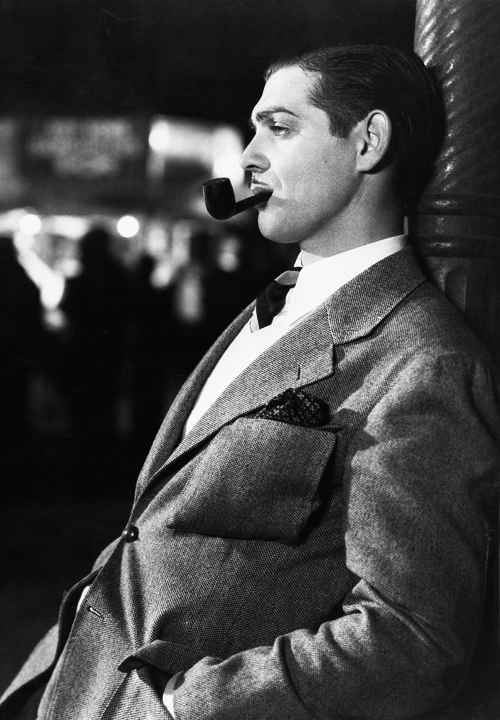

The silent star of this early talkie is Gable’s traveling suit: a sporty single-breasted number cut from a supple medium-toned tweed and featuring just about every bell and whistle in the tailor’s manual. As befits its practical purpose, the coat is a load-bearing garment, carrying massive bellowed hip pockets for the portage of such essentials as Warne’s pipe tobacco, whiskey flask, jackknife, and frugally nutritious carrots. Of particular delight is the vast bellowed parallelogram of a flapped breast pocket, into which Gable thrusts his hanks with masterful proto-sprezzatura. From astern, the coat sports a lavishly shirred yoke and an inverted box pleat tucked into a half-Norfolk belt - a true “action” back that Gable puts though its paces throughout the movie, heaving his leather suitcase (and occasionally his co-star) without straining a seam. The trousers are roomy, high-waisted and pleated, with cuffed legs wide enough that Gable is able to roll them above his knees to ford a stream.

While clearly cut for ease, the suit is not inelegant. Its broad-shouldered and heavily draped silhouette is bulky, but far from shapeless. Indeed, with its bulging pockets, rolling lapels, shirred sleeveheads (perfectly echoing the yoke), and luffing trousers, it fairly ripples with an expressive energy that the waist button sometimes seems barely able to contain. It’s not as famous as that other great transcontinental sartorial icon - Cary Grant’s North By Northwest suit - but it deserves to be. Easy wearing for hard living, Gable’s rumpled tweed is more in line with the realities of travel than the polished perfection of Grant’s granite worsted. It’s perhaps not ideal for martinis in the first class lounge, but it’s perfect for catching a few winks in coach, and isn’t that where most of us tend to find ourselves?

The rest of Gable’s ensemble is worth noting as well. His putty trenchcoat is straightforward enough, but the subtly endearing manner in which he carries it - thrown roughly over the shoulder rather than genteelly folded over an arm - captures something of how both Warne the character and Gable the man could be simultaneously hailed as “The King” and beloved as a Man of the People. His houndstooth scarf adds just the right dash of pattern, and just the right touch of warmth when given to a chilled (and still chilly) Ellie. A cream V-neck sweater and light argyle socks brighten and further informalize the outfit. Gable’s tie is a scant 3” wide, giving the lie to a yellowed sartorial adage about proportion: while a wide tie will indeed never be comfortably framed by narrow lapels, the opposite arrangement is actually quite classic. Indeed, voluptuous lapels and swelled chests like Gable’s generally benefit from the astringent note of a narrower tie and its smaller knot.

The white shirt Warne infamously removes in his and Ellie’s roadside bungalow is itself a rather perfect specimen, neither billowy nor binding, with a generously sculpted collar that looks just the right bit askew even when buttoned. The extravagantly trimmed silk pajamas they both change into before chastely settling into their respective twin beds are among the less-likely contents of Warne’s small suitcase, but observant viewers will appreciate that Gable makes a subtle nod to the real exigencies of travel dressing the next morning, when he swaps his sweater for the suit’s vest, trades his silk foulard handkerchief for white linen, and changes out his Royal Army Medical Corps repp tie for the Staffordshire Yeomanry. Voilà - a new man!

To the modern eye, Gable’s fedora is the most saliently old-fashioned element of his outfit, but because its soft high crown looks so good on him - because he’s clearly having so much fun with it, flipping its protean brim like an extra set of eyebrows - it’s the kind of hat that makes men who’d never consider wearing one quietly wonder if they could pull it off. And why not? There’s certainly no better time to experiment with one’s look than while on the road, surrounded by indifferent and passing strangers.

Despite all these delicious little sartorial perfections - or perhaps because of them - Peter Warne comes across as a man who enjoys dressing as a matter of course and competence rather than finicky obsession. His rugged presentation contrasts subtly but sharply with his fellow bus rider, the lubriciously scheming Mr. Shapeley, contemptibly prim in his pinned collar, fob chain, and boutonniere. Indeed, Warne’s ultimate rival for Ellie’s affections - the gold-digging playboy “King” Westley - is a villain almost wholly sketched in his handful of scenes by overly fastidious accoutrements: kid gloves, high stiff collar, spats, a twirled mustache, and a (practically twirling) cane.

Peter and Westley’s final showdown is not one of country bumpkin vs. urban sophisticate, however, for Warne knows how to play that game too, and far better. Mistakenly thinking himself callously rejected, an embittered Peter nevertheless brushes off his Sunday best to meet Ellie’s father on the day of her society wedding to Westley, and it is exquisite. The dandy groom’s florid wedding rig, while formally unimpeachable, renders him hopelessly effete and anachronistic in contrast to Warne’s modern, muscular understatement: a simple, impossibly sinuous three-piece suit in midnight flannel, single-breasted and peak-lapelled, punctuated with a crisp white shirt and square, and finished with an Old Harrovian tie. With this final triumphant ensemble, Gable epitomizes elegant minimalism as consummately as his traveling suit embodies the knockabout charm of casual sportswear, so proving him a master not of a specific look, but of the entire art - then emerging, now canonical - of fine men’s dress. Needless to say, he gets the girl.

The first film to win the “Big Five” Oscar awards - Best Picture, Actor, Actress, Director, and Screenplay - It Happened One Night [1934] actually happens over several nights of a bus, automobile, and shoe leather journey from Miami to New York, undertaken by Clark Gable’s hard-boiled newshound Peter Warne and his journalistic quarry Ellie Andrews - a runaway heiress played with iconic pluck by Claudette Colbert. This is the movie everyone knows for having collapsed undershirt futures when Warne undresses to reveal a bare chest, but its real sartorial significance lies not in what Gable doesn’t wear, but in what he does. His attire throughout the film is a case study in the form and function of classic menswear, not least because the film was a commercial blockbuster, doing much to set the style for a decade that’s set the style ever since.

From a wainscoted yacht off Miami, to bustling modern cities of news stands and phone booths, to bucolic idylls of moonlit haystacks and general stores, to a formal garden wedding at a baronial estate, It Happened One Night’s locales make it something of an Apparel Arts travelogue, as atmospherically rendered and elegantly populated as Laurence Fellows’ idealized illustrations. It is perhaps a road movie even before it’s a screwball comedy or even a love story, and the style of its male protagonist is suffused with the giddy romance of a mode of travel only recently made possible by the internal combustion engine. The act of traveling today may conjure little but fast food and flight delays, and the clothes we wear to endure it tend to be chosen largely as comfortable swaddling, but watching Peter Warne make his way up the eastern seaboard and into Ellie Andrews’ heart reminds us that it doesn’t have to be this way.

The silent star of this early talkie is Gable’s traveling suit: a sporty single-breasted number cut from a supple medium-toned tweed and featuring just about every bell and whistle in the tailor’s manual. As befits its practical purpose, the coat is a load-bearing garment, carrying massive bellowed hip pockets for the portage of such essentials as Warne’s pipe tobacco, whiskey flask, jackknife, and frugally nutritious carrots. Of particular delight is the vast bellowed parallelogram of a flapped breast pocket, into which Gable thrusts his hanks with masterful proto-sprezzatura. From astern, the coat sports a lavishly shirred yoke and an inverted box pleat tucked into a half-Norfolk belt - a true “action” back that Gable puts though its paces throughout the movie, heaving his leather suitcase (and occasionally his co-star) without straining a seam. The trousers are roomy, high-waisted and pleated, with cuffed legs wide enough that Gable is able to roll them above his knees to ford a stream.

While clearly cut for ease, the suit is not inelegant. Its broad-shouldered and heavily draped silhouette is bulky, but far from shapeless. Indeed, with its bulging pockets, rolling lapels, shirred sleeveheads (perfectly echoing the yoke), and luffing trousers, it fairly ripples with an expressive energy that the waist button sometimes seems barely able to contain. It’s not as famous as that other great transcontinental sartorial icon - Cary Grant’s North By Northwest suit - but it deserves to be. Easy wearing for hard living, Gable’s rumpled tweed is more in line with the realities of travel than the polished perfection of Grant’s granite worsted. It’s perhaps not ideal for martinis in the first class lounge, but it’s perfect for catching a few winks in coach, and isn’t that where most of us tend to find ourselves?

The rest of Gable’s ensemble is worth noting as well. His putty trenchcoat is straightforward enough, but the subtly endearing manner in which he carries it - thrown roughly over the shoulder rather than genteelly folded over an arm - captures something of how both Warne the character and Gable the man could be simultaneously hailed as “The King” and beloved as a Man of the People. His houndstooth scarf adds just the right dash of pattern, and just the right touch of warmth when given to a chilled (and still chilly) Ellie. A cream V-neck sweater and light argyle socks brighten and further informalize the outfit. Gable’s tie is a scant 3” wide, giving the lie to a yellowed sartorial adage about proportion: while a wide tie will indeed never be comfortably framed by narrow lapels, the opposite arrangement is actually quite classic. Indeed, voluptuous lapels and swelled chests like Gable’s generally benefit from the astringent note of a narrower tie and its smaller knot.

The white shirt Warne infamously removes in his and Ellie’s roadside bungalow is itself a rather perfect specimen, neither billowy nor binding, with a generously sculpted collar that looks just the right bit askew even when buttoned. The extravagantly trimmed silk pajamas they both change into before chastely settling into their respective twin beds are among the less-likely contents of Warne’s small suitcase, but observant viewers will appreciate that Gable makes a subtle nod to the real exigencies of travel dressing the next morning, when he swaps his sweater for the suit’s vest, trades his silk foulard handkerchief for white linen, and changes out his Royal Army Medical Corps repp tie for the Staffordshire Yeomanry. Voilà - a new man!

To the modern eye, Gable’s fedora is the most saliently old-fashioned element of his outfit, but because its soft high crown looks so good on him - because he’s clearly having so much fun with it, flipping its protean brim like an extra set of eyebrows - it’s the kind of hat that makes men who’d never consider wearing one quietly wonder if they could pull it off. And why not? There’s certainly no better time to experiment with one’s look than while on the road, surrounded by indifferent and passing strangers.

Despite all these delicious little sartorial perfections - or perhaps because of them - Peter Warne comes across as a man who enjoys dressing as a matter of course and competence rather than finicky obsession. His rugged presentation contrasts subtly but sharply with his fellow bus rider, the lubriciously scheming Mr. Shapeley, contemptibly prim in his pinned collar, fob chain, and boutonniere. Indeed, Warne’s ultimate rival for Ellie’s affections - the gold-digging playboy “King” Westley - is a villain almost wholly sketched in his handful of scenes by overly fastidious accoutrements: kid gloves, high stiff collar, spats, a twirled mustache, and a (practically twirling) cane.

Peter and Westley’s final showdown is not one of country bumpkin vs. urban sophisticate, however, for Warne knows how to play that game too, and far better. Mistakenly thinking himself callously rejected, an embittered Peter nevertheless brushes off his Sunday best to meet Ellie’s father on the day of her society wedding to Westley, and it is exquisite. The dandy groom’s florid wedding rig, while formally unimpeachable, renders him hopelessly effete and anachronistic in contrast to Warne’s modern, muscular understatement: a simple, impossibly sinuous three-piece suit in midnight flannel, single-breasted and peak-lapelled, punctuated with a crisp white shirt and square, and finished with an Old Harrovian tie. With this final triumphant ensemble, Gable epitomizes elegant minimalism as consummately as his traveling suit embodies the knockabout charm of casual sportswear, so proving him a master not of a specific look, but of the entire art - then emerging, now canonical - of fine men’s dress. Needless to say, he gets the girl.