idfnl

Stylish Dinosaur

- Joined

- Dec 6, 2008

- Messages

- 17,305

- Reaction score

- 1,260

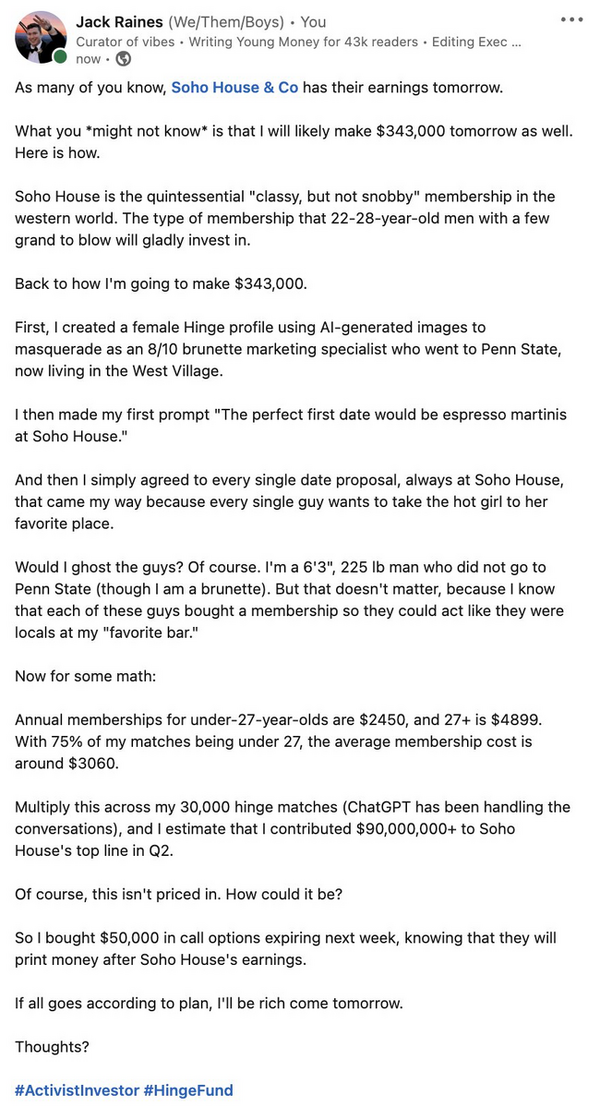

That's an interesting distinction about the cab driver.

Hypothetically, would there be a difference if the cab driver setup that ride with the intention of scooping information from the passengers? Meaning, is there a difference between happenstance and intent? I always understood it to be about intent.

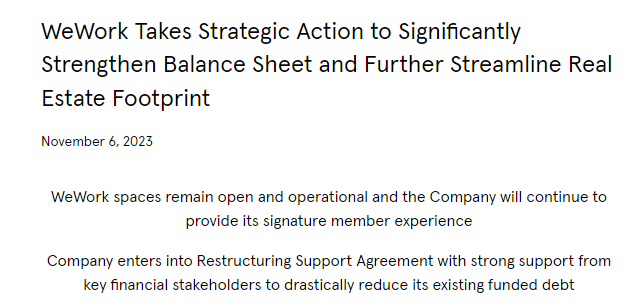

One essential element of insider trading is that the material nonpublic information being traded upon have been obtained in violation of a fiduciary duty or other special relationship giving rise to an obligation to keep the information confidential. (Simplistic illustrative example: taxi driver who trades on basis of conversation overheard in the back of his cab is not guilty of insider trading) In some factual situations that's obvious. In others it isn't.

That requirement may or may not be meaningful in the situation you guys are discussing -- just throwing it out there in case it is.

That's an interesting distinction about the cab driver.

Hypothetically, would there be a difference if the cab driver setup that ride with the intention of scooping information from the passengers? Meaning, is there a difference between happenstance and intent? I always understood it to be about intent.

Last edited: